Maya Bekhazi Noun and Japanese Ambassador to Lebanon, H.E. Matahiro Yamaguchi

Maya Bekhazi Noun and Japanese Ambassador to Lebanon, H.E. Matahiro Yamaguchi

Whether in the form of a sparkling aperitif or a digestif, sake is increasing its global market share. Versatile, unique and enigmatic, this beverage, which has its roots in Japan, complements food just as wonderfully as wine. Maya Bekhazi Noun of The Food Studio gives us a complete product overview with the help of Japan’s Ambassador to Lebanon, H.E. Matahiro Yamaguchi

There are four main styles of sake or designations: junmai, honjozo, ginjo and daijingo. The sake falls into one of these categories, depending on the percentage of rice-grain polishing and whether the sake has had distilled alcohol added.

Junmai: This purest form of sake remains unpolished, light and refreshing on the palate.

Honjozo: The sake must have had a minimum of 30 percent polishing, with perhaps a small amount of alcohol added to lighten and add fragrance.

Ginjo: In this category, 60 percent remains unpolished. The sake is fruity and floral, light and refreshing.

Daiginjo: Here, 50 percent or less remains unpolished. The sake is made in smaller quantities, using more traditional methods, with a richer flavor and aroma profiles, displaying complexity and finesse.

There is a special fifth category for unpasteurized sakes, called nama, which encompasses all four of the above styles.

The process

Sake rice is a special rice used for brewing sake, which is usually stronger and used only for this purpose. The core of the rice grain is rich in starch, while the outer layers, which contain higher concentrations of fats, vitamins and proteins, are milled away in a polishing process, leaving only the starchy part of the grain.

The rice-polishing ratio measures the degree of rice polishing. For example, a rice-polishing ratio of 60 percent means that this proportion of the original rice grain remains and 40 percent has been polished away. Water is involved in almost every major process of sake brewing, so ensuring its quality and purity is essential.

Brewing

Sake is produced by the multiple parallel fermentation of rice. The rice is polished and then rested, before being washed. Later, it is steamed and then left to cool, after which it is divided into portions for different uses.

Koji – the microorganism or ‘the mold’ – is added to the steamed rice, which is then left to ferment for between five and seven days. After this initial fermentation period, water and yeast culture are added to the rice mixture and left to incubate for about seven days. The pre-incubated mixture of steamed rice, fermented rice and water is then added to the fermented mixture in phases. This is then left to ferment for between two and three weeks.

Following the fermentation process, sake is then extracted through a filtration process. For some types of sake, a small amount of distilled alcohol is added. In cheap sake, a large amount of alcohol might be added to increase the volume of sake being produced. The remains of the sake are carbon-filtered and pasteurized, then allowed to mature before being diluted with water to lower the alcohol content from around 20 percent to 15 percent before final bottling.

Maturation

Like other brewed beverages, sake benefits from a period of storage. The maturing process for sake is between nine and 12 months.

Pairing

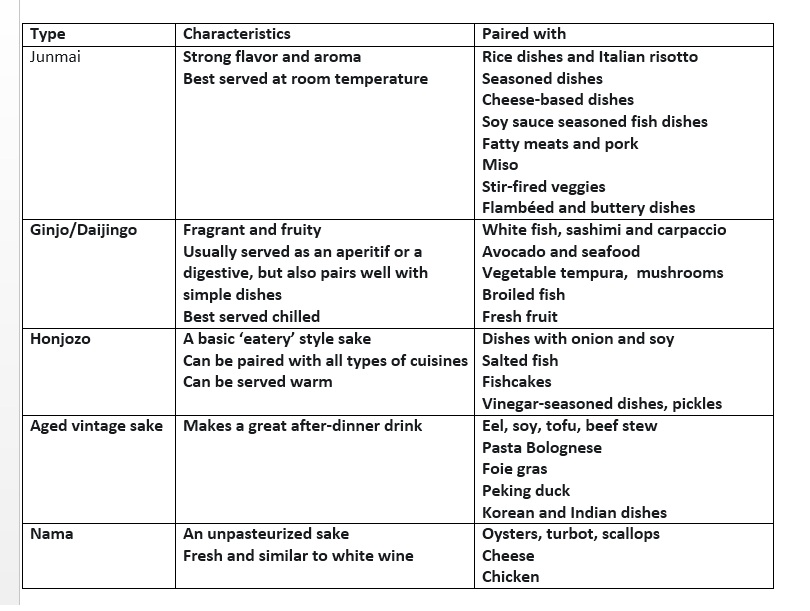

Gone are the days when sake was only paired with sushi or other Japanese foods; today this increasingly popular beverage features in cocktails and is often paired with non-Japanese cuisines. Complex parameters for pairing food and sake include: identifying fragrance; sweet vs. dry; acidity; texture; freshness-lightness vs. settled-earthiness; umami complexity; and refinedness vs. solidity and simplicity.

Balance: Rich sake complements rich cuisine, while clean, smooth sakes pair well with light cuisine. Dry sake makes a good accompaniment to salty dishes.

Harmony in sake and food is certainly achievable. Think of those occasions when a meat dish prompts a craving for red wine.

The Wash is the refreshing feeling that you get at the end of certain sakes, which, if paired correctly, have the effect of cleansing the palate in between mouthfuls. It resets the palate so that you can enjoy the following bite of food and enhances the flavor of whatever comes next.

Temperature is important when it comes to sake. While usually served at room temperature, it can also be served chilled or warmed.

Facts

Facts

Sake’s complexity, elegance and price point all determine how polished the grains of rice are that go into it. The more polished the sake, the cleaner the taste. The rice powder that is a by-product of the polishing is very often used for making rice crackers or Japanese sweets.

Records show that sake production began in Nada almost 700 years ago in 1330. Nada Gogo is the largest sake-producing region in Japan, with its breweries accounting for just over one-quarter of the country’s entire sake production. Nada’s sake has four distinct characteristics that make it unique:

The rice plantation: known for the density of the white core, low protein content and consistency in size and texture.

Miyamizu water: A hard water that flows off of Mount Rokko, which makes strong, thick sake.

Tanba Koji: Tamba has a long tradition of sake production.

Weather: Cold winds which blow from Mount Rokko are used as a natural coolant to slow the fermentation process.

Rita Ghantous is a hospitality aficionado and a passionate writer with over 9 years’ experience in journalism and 5 years experience in the hospitality sector. Her passion for the performance arts and writing, started early. At 10 years old she was praised for her solo performance of the Beatles song “All My Love” accompanied by a guitarist, and was approached by a French talent scout during her school play. However, her love for writing was stronger. Fresh out of school, she became a freelance journalist for Noun Magazine and was awarded the Silver Award Cup for Outstanding Poetry, by The International Library of Poetry (Washington DC). She studied Business Management and earned a Masters degree from Saint Joseph University (USJ), her thesis was published in the Proche-Orient, Études en Management book. She then pursued a career in the hospitality industry but didn’t give up writing, that is why she launched the Four Points by Sheraton Le Verdun Newsletter. Her love for the industry and journalism led her to Hospitality Services - the organizers of the HORECA trade show in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Jordan, as well as Salon Du Chocolat, Beirut Cooking Festival, Whisky Live and other regional shows. She is currently the Publications Executive of Hospitality News Middle East, Taste & Flavors and Lebanon Traveler. It is with ultimate devotion for her magazines that she demonstrates her hospitality savoir-faire.

© 2024 Hospitality News Magazine. All rights reserved. Designed and Developed by Born Interactive